Register for free and continue reading

Join our growing army of changemakers and get unlimited access to our premium content

Rewind in your mind for a moment to October 2021. It was the culmination of a build-up to COP26 that had lasted two years, and the momentum was palpable. The climate crisis was headline news in tabloids, as were the solutions and the people dedicating their lives and careers to sustainability. Businesses were making announcements every day. People from all walks of life were asking for more information on what a COP entails.

The Summit itself came with more of that same energy and, while the final texts are understandably a source of major disappointment for those in the most-affected nations, the general consensus seems to be that strong progress was made on many fronts – including forests, methane and cleantech.

As has been said by several environmental activists and sustainability thought-leaders already, the mood fell somewhat flat post-COP. The Biden Administration held a huge oil and gas lease sale for the Gulf of Mexico. Fuel spills were confirmed in Hawaii, then Thailand, Ecuador and Peru. The UK’s Oil and Gas Authority gave consent to the Abigail oil and gas field. The EU is preparing to label natural gas “green” in its new finance taxonomy.

These stories, and a great many more, have added to a growing sense of anger at the gap between talk and action on climate, when we are repeatedly told we are running out of time.

We are also increasingly seeing the physical impacts of the climate crisis edging closer to our homes (in the global north at least, for much of the global south, this has been the reality for decades). Add this to the fact we are largely online a lot more and dealing with the ongoing anger and grief that comes with living in a pandemic and distrusting national leadership (this now has its own terminology, ‘outrage burnout’), and you have a recipe for every announcement being put on trial in the court of public opinion.

Like a brand caught in the headlines

Greenwashing is neither a new tactic nor a new term; it was coined by environmentalist Jay Westerveld in 1986, following years of television and print ads from oil majors including Exxon. But, as with climate denialism, it has evolved in line with changing ideas of business purpose and ever-more digitised advertising.

The good news is that this anger is finally being converted into frameworks with some legal teeth. Here in the UK, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) announced last month that it will undertake its first official investigation into greenwashing, with an initial focus on fashion. Brands found to be flouting its Green Claims Code could face fines and other penalties.

This is, of course, welcome, given how fashion brands have been very trigger-happy with adding environmental clothing to products in recent years. One 2021 study of the websites of 12 of the biggest British and European fashion brands, including Asos, H&M and Zara, found that 60% of the environmental claims could be classed as “unsubstantiated” and “misleading”.

The bad news is that so much greenwashing is still going on, and fashion is far from the only culprit.

Fossil fuel majors, as they regularly are, have been in the spotlight over greenwashing – and so have firms in other sectors that seem willing to enable them. In January, Vice accused Shell of delivering a carbon capture solution that emits more CO2e than it captures. Edelman and other PR and advertising firms were hauled over the coals by campaigners over continued contracts with oil and gas giants.

Other usual suspects have also been in the news in January. Airport Authority Hong Kong was dubbed hypocritical for launching its inaugural green bond, without measures to cap growth, for example. Keurig Canada was fined $3m for misleading claims on coffee pod recycling. And the debate over whether ESG funds are actually ethical or sustainable rolled on.

But even self-styled “sustainable” brands are also feeling the heat. In a story that amassed more than 18,000 shares on LinkedIn, plant-based brand Oatly saw one of its advertising campaigns banned by the UK’s Advertising Standards Authority for overstating the environmental benefits of alternative milks. Oatly had already faced a major ethical scandal in 2020 after signing a deal with Blackstone – a private equity firm headed by Trump donor Stephen Schwartzman.

And, just last week, action group Plastics Rebellion filed a complaint to the UK’s ASA concerning B Corp certified innocent Drinks. The Coca-Cola-owned drinks brand recently ran a TV advertisement showing a man and otter cleaning up rubbish, but Plastics Rebellion has argued that innocent is manufacturing 32,000 plastic bottles every hour, thus contributing to plastic pollution.

Get ahead of the curve, for good

Sustainability predictions have, for a few years now, warned that greenwashing in most sectors is likely to get worse before it gets better, with companies keen to appeal to increasingly green-minded consumers/clients/investors but less keen to transform their businesses and even less keen to think about changing systems that have served them for decades.

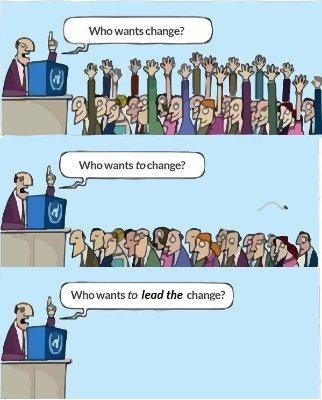

I am sure we will all have seen the below meme:

But the fact is that we are now at a moment where stakeholders will not be appeased by a statement with jargon terms they don’t really understand, or a sustainability report with data already 12+ months out of date. We’re all a lot more cynical, critical, angry, distrusting and – perhaps most importantly – online. With a little searching, we can see where a business’ statements don’t match up with its future investment plans, or its historic actions.

With that in mind, it won’t just be the loss of one or two customers at stake, but potentially sizeable fines in the courtroom and reputational damage that just will not shift.

On the latter, it would be easy to think that in this digital age with rapidly shifting news cycles, a single blip will be swiftly forgotten. Yet, when we think of purpose-washing, the first example that springs to mind for many will be the 2017 PepsiCo commercial starring Kendall Jenner.

It is, indeed, a landscape full of pitfalls for any brand. The CMA’s Green Claims Code, mentioned above, serves as a handy navigational tool. It covers six initial principles (which are worth checking your brand claims against if this blog has sparked any feelings of panic):

- Accuracy

- Clear, unambiguous and understandable claims

- Not omitting important information

- Ensuring that ‘fair and meaningful’ comparisons can be made between products

- Covering the impact of a product’s whole life-cycle

- Ensuring that claims can, if questioned, be backed up with “robust, credible and up-to-date” evidence

Critics will not be quick to forget. They will either conclude that your brand is too incompetent to make clear and credible statements, or that it is deliberately misleading them. It’s hard to decide which is worse.

Please login or Register to leave a comment.