Register for free and continue reading

Join our growing army of changemakers and get unlimited access to our premium content

The study of almost 500 companies found that a growing number are demonstrating increased focus on advocacy, but that most are being held back by failing to address certain negative climate policy influences

Rankings are a prominent part of any form of media coverage. Whether a website is ranking the Star Wars films from best to worst or a sports broadcaster is updating its weekly “power” ratings of players, they provide a simple and easily digestible way for consumers and other stakeholders to gain a better understanding of opinions and scientific studies.

This tried and trusted method is no stranger to the sustainability professional. Many have trawled through their own data in a bid to place their company into the echelons of the Dow Jones Sustainability Indices or CDP’s Climate A list.

As sustainability continues to rocket up the financial, public and policy agendas, the demand for information on corporate climate action grows. Rankings continue to provide a valuable and succinct way to showcase performance.

However, there is a growing sense of frustration amongst the corporate community that some rankings aren’t providing clarity on efforts to transition to a sustainable and low-carbon economy.

Retail roundup

At the start of the month, Which? published its inaugural sustainability ranking, which covered 11 of the UK’s largest supermarket chains. Scores were allocated based on data that supermarkets either published publicly or provided to Which?, concerning greenhouse gas emissions, plastic waste and food waste.

Coming in last place, with an overall score of just 29%, was Iceland foods. Which? found that while Iceland Foods is outperforming most competitors in terms of reducing food waste, it did not report how much of its own-brand plastic packaging is recyclable, thus losing points. Which? also scored Iceland Foods last in terms of emissions. “Iceland’s in-store freezers need a lot of energy to run, though it does buy 100% renewable electricity for its UK sites,” said Which? in a statement.

The low score on plastic will have raised some eyebrows, given Iceland Foods’ commitment to removing all consumer-facing plastic packaging from all own-brand lines by 2023. The commitment is regarded as one of the most ambitious in the UK’s grocery retail sector.

Iceland’s managing director Richard Walker said the firm “does not recognise the data used by Which? or accept the low ranking on sustainability that the magazine has accorded us”.

“Far from ‘working with the supermarkets to acquire the most accurate and comparable data available’, as they claim, Which? have chosen to ignore repeated warnings by us and our legal advisers that their methodology was completely flawed,” Walker told edie.

“Their calculation of carbon intensity grossly misrepresents Iceland because it is based on retail spend rather than sales volumes, penalising supermarkets that sell at low prices. It also fails to take account of our 100% usage of renewably generated electricity. Their calculation of plastic intensity is equally incorrect, and bears no relation to our own audited and published data on plastic usage, which is used to calculate the packaging taxes we pay.”

Which? maintains that its analysis is “in-depth”. It has stated that it will repeat the league table each year.

Another firm that has criticised the Which? rankings is Marks and Spencer (M&S). The rankings claimed M&S was unable to provide food waste data in a suitable format and was also producing more plastic packaging, and more emissions, than most of its competitors.

This result will have come as a surprise to some shoppers. M&S has been working for more than a decade towards a vision of becoming the UK’s most sustainable retailer, and recently updated its long-standing ‘Plan A’ sustainability strategy.

A spokesperson for M&S told edie: “This research is one industry benchmark based on certain criteria and our ranking does not fairly reflect our sustainability ambitions or achievements to date.”

Sportswashing

Another recent rankings system to face criticism comes from the BBC. The broadcasting giant published a sustainability league table based on Premier League football clubs. While Tottenham and Liverpool topped the rankings, the decision to place Manchester City in third has raised eyebrows.

Points in the rankings are awarded for policy and commitment, clean energy, energy efficiency, sustainable transport, single-use plastic reduction or removal, waste management, water efficiency, plant-based or low-carbon food, biodiversity, education and communications and engagement.

Manchester City Football Club does indeed have some ambitious sustainability and community targets, including a net-zero target for 2030. However, discussions across social media have argued that the rankings rely on “weak scoring and weighting, self-reporting, absence of more material impacts including ownership wider sustainability credentials”, namely in reference to Manchester City being owned by the Abu Dhabi royal family, which is still economically reliant on oil and gas.

Net-zero rankings

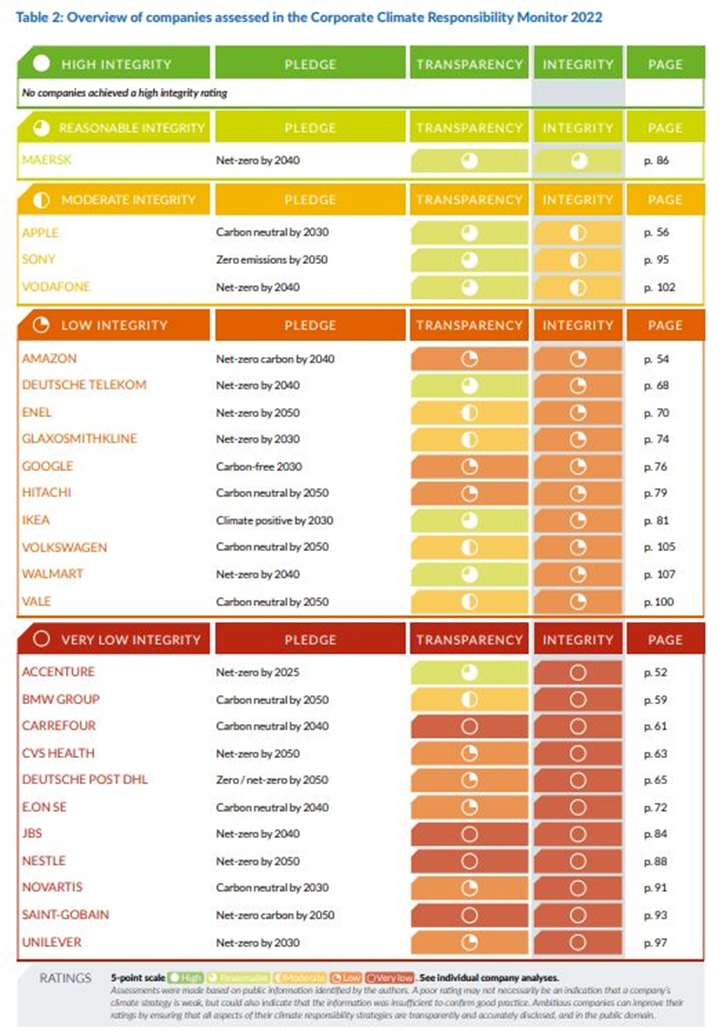

Also this month, analysis from Berlin-based organisation the New Climate Institute and non-profit Carbon Market Watch, on corporate net-zero targets, has been met with mixed reaction.

The two organisations assessed the scope of the long-term net-zero commitments of 25 large businesses across a range of sectors including telecommunications, logistics, consumer goods, energy and automotive. It found that these net-zero targets cover, on average, just 40% of annual greenhouse gas emissions, with the likes of Unilever, Nestle and BMW Group named among the worst offenders.

The rankings have proven contentious amongst sustainability professionals. Despite all 25 firms using CDP and SBTi frameworks to report on their net-zero commitments, the report offers lower scorings than either of those initiatives.

Those within the spectrum of corporate sustainability were quick to point out that while scrutiny is essential, the rankings are focusing on those attempting to reach net-zero through action, rather than concentrating on corporate inaction.

“Now I’ve been on the end of enough corporate benchmarking to know sometimes they can be wrong; occasionally ‘right but unfair’; and often ‘not quite accurate but have more than a kernel of truth’ to them” Mike Barry, director of Mikebarryeco, said on LinkedIn.

“I’m sure individual brands will raise their specific concerns but overall the report does a good job of challenging the orthodoxy, which few claimed to be perfect but which possibly too many had been seduced into believing was ‘good enough’. Above all, its recommendations for change are framed clearly and constructively to allow one to come back with a ‘build’ or ‘counter proposal’ to make the pathway to corporate net-zero more effective, more robust and more transparent. It’s too important to get wrong!”

A lists

The contentious issues surrounding these types of rankings serve to highlight the sheer task at hand for sustainability professionals. These individuals and small teams are steering monumental change through some of the world’s biggest corporates – indeed, the companies ranked by Carbon Market Watch account for some 5% of annual global emissions.

But sustainability is constantly evolving. Environment used to sit in a silo from community or social-focused initiatives, but for many businesses, these two areas are merged under a CSR or ESG umbrella and thus are now viewed in tandem. Efforts to decarbonise have moved from iterative to science-based and as the urgency to combat the climate crisis increases, so too does the complexity of forging out net-zero targets.

What this does highlight is how demand on corporates is changing. Setting a science-based and net-zero target is now viewed as a prerequisite to responsible business. Corporates must now be able to prove and demonstrate that they can deliver against new and ambitious targets.

It is here where disclosure becomes are a crucial tool in a business’s approach to sustainability.

CDP has been leading the charge on corporate disclosure for more than 20 years. The organisation’s long-standing A list rankings of environmental disclosure has long been celebrated by businesses that are able to score a prestigious “A” ranking.

For CDP’s global director of corporations and supply chains, Dexter Galvin, it is key that corporates are collecting and disclosing data through global and standardised frameworks to provide better clarity for key stakeholders, such as investors.

“Standardisation and harmonisation of data in this space are critical,” Galvin tells edie. “I think that there are too many, I would say arbitrary, assessments of an organisation’s sustainability performance, but it’s not fair to expect people to be able to decipher what an organisation is doing, by looking at the PR hosted on their website.

“It’s always good that organisations are shining a light on what companies are doing, and that’s absolutely critical, but there’s a lot of value for a standardised disclosure framework to ensure that the highest quality of information gets out there.”

CDP has had more than 20 years of gathering data from corporates, and Galvin believes that this has become an “incredibly useful” tool for organisations to have informed discussions with the investor community.

Indeed, Galvin believes that disclosure has become “business as usual” for larger corporations, but that a trickle-down effect is needed to help smaller organisations.

Where some businesses are falling down, Galvin claims, is on the supply chain. Recent CDP research found that a little over one-third of large corporates are engaging with suppliers on the climate crisis and carbon reduction, despite value chain emissions being more than 11 times greater than emissions resulting from operations in some cases.

Glance across the CDP’s Climate A list and you’ll see some interesting names. Tobacco giant Philip Morris International scored As across all three categories, climate change, forests and water. Austrian textile company Lenzing AG also scores As across the board, despite other rankings linking the firm with dangerous supply chain practices. Lenzing has since moved to new supply chain management practices off the back of that report.

Galvin stresses that CDP ranks corporates purely on environmental performance and that calling for these types of sectors to disclose helps them on their sustainability journey by ensuring they don’t get a “free pass” while other companies face more scrutiny.

It is clear that no company is perfect, and all can make improvements. But they are all operating in a broken economy where trade-offs are inevitable, either deliberate or otherwise.

As such, rankings are in danger of becoming too two-dimensional for a movement with so many factors at play. The danger is that consumers and stakeholders glance across these rankings and summarise who is good and who is bad on what can be flawed and weighted data.

Galvin believes that businesses will need to be able to dispute claims, either through rankings, reports, or other means, with data that showcases not just ambitious strategies, but also year-on-year improvements across key areas of sustainability.

“When I started at CDP in 2008 what we were collecting then would be very much out of touch with what is required now, because the area has changed so much,” he adds. “For us, it is always about pushing organisations out of their comfort zones and into the next area, so moving forward, it’s going to be even harder for organisations to get an A on our rankings.

“The evolution of reporting over time isn’t just about collecting the data of yesterday more efficiently, it’s about making sure that we’re signaling the direction of travel to organisations and those organisations that respond well to us. It’s one thing to set an ambitious 1.5C science-based target and get it approved. It’s quite another thing to have that transition plan detailed and embedded in your organisation, that’s where we’re focusing on now, how are companies deliver action through transition plans.”

Matt Mace

Please login or Register to leave a comment.