Register for free and continue reading

Join our growing army of changemakers and get unlimited access to our premium content

The question is important because it could determine the fate of many companies that are attempting to change our relationship with the goods we use in our lives and which, historically, we have owned. At a recent workshop I attended, the question provoked an emotional response, especially in relation to certain types of products. For example, most mothers refuse to countenance the idea of purchasing a refurbished baby stroller because – regardless of guarantees for its quality – they only want the best for their new-born. But if a company provides a 100% guarantee for a product, does it always matter if it has been used before?

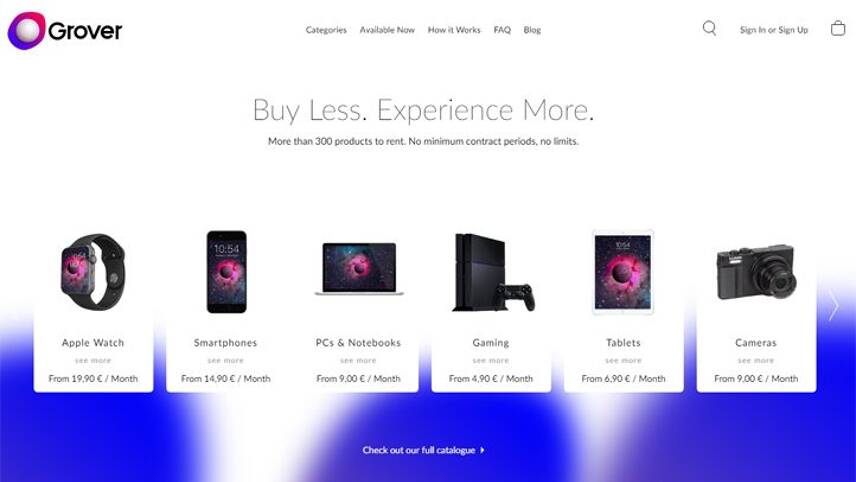

A company called Grover, which styles itself as the payment method for the circular economy, is working to change such preconceptions. It operates in the technology space and provides an easy-to-use flexible subscription platform for mobile phones, cameras, drones and many other products. Its pitch is straightforward: the most important element of any product is its function and a guarantee that it will continue to perform for a certain period. In this context, it believes that pre-use should be irrelevant. Grover tells its client that some items it rents may be refurbished but promises they will function (and look) like a new product.

In this way Grover supports higher asset utilisation and longer life cycles, ensuring there are fewer obsolete products lying in closets and drawers waiting to be thrown away. Also, Grover addresses the tension between sustainability and the circular economy by facilitating continued consumption without depleting resources and creating waste.

Grover’s message seems to be getting through. The company attracted a solid customer base in its short lifetime. It has also teamed up with MediaMarkt, Europe’s largest retailer, to provide an integrated rental function (instead of buying a product) on the retailer’s website. It is noteworthy that many of its clients are young: there appears to be an emerging acceptance that it is no longer necessary to own products outright.

The breakdown of Grover’s customer base indicates the potential for its circular economy model. Around 10% of Grover’s users ultimately buy the product: they are gaining access to an item that they wouldn’t otherwise be able to afford. A further 10% of customers use Grover because it enables them to try out new products without having to commit to a purchase; some of these people may be early adopters who are eager to have the latest product and therefore value the ability to upgrade frequently.

However, the majority of users simply enjoy the flexibility that Grover offers to meet their short-term needs: it’s possible just to rent a hover board for your kids over the summer holidays, for example.

Grover’s business model is relatively straightforward by tech standards. Items are priced at a monthly rate that ensures the cost of the item is covered within an 11-month cycle – all revenue after this is profit: typically an item might be in circulation for between four and six cycles. Grover has obtained insurance not only against customer damage to its products but also against loss of cash flow, giving it greater certainty and stability than most young companies. This is possible because it has a legal advantage over traditional consumer finance companies as it retains ownership of its goods: if customers don’t return them, they are committing theft.

From a financing perspective, Grover’s model is also interesting. Typically, when a consumer’s purchase of a product is financed, an assessment of the risk of non-payment by the consumer (their credit worthiness) is key, as this is the main source of repayment of the loan. Grover’s model is different because the consumer does not borrow money: instead Grover is the borrower and uses the finance to buy products. Consequently, the customer’s credit worthiness is unimportant. Instead, the asset itself becomes the focus – the question is whether Grover can find customers and convince them to rent a product for another cycle and keep it in economic use. Judging by its growing customer base, Grover seems to be doing this well. The company’s model also means it can obtain borrowing attractively, as debt can be secured on the rented assets, giving lenders access to the consumer finance market and the security of the tech products Grover rents out.

Grover, therefore, seems well positioned for the future. All that remains is for the critical question to be answered: can we get over our fear of second hand?

Gerald Naber is vice president of sustainable finance at ING

Please login or Register to leave a comment.