This premium content is exclusive to edie Members.

To find out more about edie Membership, please click below.

If you are an existing member, login here

Carbon credits are one of the most contentious tools that a corporate can utilise in efforts to deliver on ambitious decarbonisation pledges. Those attempting to embed integrity into the markets argue that corporate support can spur seismic change that delivers restoration, captures carbon and adds social value to certain communities. To date, though, tangible cases are few and far between, leading many green groups and NGOs to warn that carbon offsetting merely gives businesses a license to carry on emitting as usual.

This has created a tug-of-war in which corporates are caught in the middle. Some are keen to dip their toes into carbon markets, drawn in by progress and new frameworks that suggest that these markets do have a role to play in reaching net-zero. But many others have shied away, wary of the historic side-effects of associating themselves with carbon credits, such as reputational damage and investing in low-quality offsets that make no real difference.

As such, 2024 is shaping up to be a deciding year for carbon markets.

Research from the Ecosystem Marketplace found that the average credit prices in voluntary carbon markets are higher than they have been in the last 15 years, but that overall trade volumes are down by 51% compared to the high witnessed in 2021.

According to new BloombergNEF (BNEF) research published on Tuesday (6 February), the market is now in a state of flux and the frameworks, policies and corporate involvement that happens in 2024 could make or break the market.

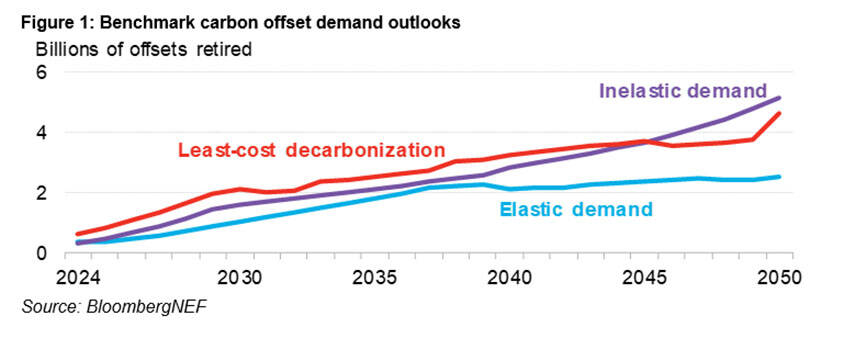

BNEF notes that the markets will respond to varying levels of “elastic demand” that could create a huge spike in carbon credit purchases over the next six years.

BNEF identifies three market transitions that would lead to different levels of demand for carbon credits. Under a High-Quality Market Scenario, integrity issues in the offset market are resolved and offset demand becomes “inelastic”. This would see prices reach $20/ton in 2030, (up from around $7/ton currently) but begin rising as milestone years for net-zero goals approach. By 2050, credits reach $238/ton with the market valued at $1.1trn annually.

That is very much a best-case scenario, however, and ongoing issues plaguing the market suggest that BNEF’s “Voluntary Market Scenario”, whereby issued aren’t resolved, is more likely. BNEF notes that the current market is heavily oversupplied – to the tune of nearly 50% in 2023 – and many companies have started to turn their backs on the markets for fear of greenwashing.

Under this scenario, prices reach $13/ton in 2030 and $14/ton in 2050 and would fail to dispel concerns over credit quality and that organisations can merely pay to pollute. The market would peak under this scenario at $34bn annually in 2050, up from $2bn today.

If this “elastic demand” continues, companies could be purchasing one billion offsets annually by 2030, peaking at around 2.5 billion in 2050.

A final, “Removal Scenario” would see companies only buy carbon removals and credits that are interchangeable with other forms of abatement, which leads to concerns over a race to the bottom, dictated by cheap prices.

BNEF’s head of sustainability research Kyle Harrison says: “There is no shortage of governments and investors that are eager to monetise emission reductions through carbon credits and channel financing towards projects.

“But if buyers can’t trust the quality of the credits they’re buying and risk greenwashing accusations, then the market will never reach its potential. Credits will never be more than discretionary spend in this case.”

Market fluctuations

Last year, research from Ecosystem Marketplace found that the companies engaged in the voluntary carbon market are surpassing their counterparts in key areas of climate action, accountability and ambition, rather than simply using credits as a method to ‘buy their way out’.

In 2022, 7,415 companies publicly disclosed their activities to the CDP Climate Change program, mainly covering their actions in 2021. Among these, 822 companies (11%) participated in voluntary project-based carbon credits as buyers (736) or originators (86), while 55 companies used project-based carbon credits solely for compliance purposes. According to the findings, 59% of buyers in the market reported a decrease in gross emissions on an annual basis due to reduced emissions and/or increased utilisation of renewable energy, while this reduction was reported by only 33% of businesses that were not engaged in carbon markets.

However, issues remain over the integrity of the voluntary carbon markets, with many firms investing in cheap “junk credits”, while high-profile investigations in 2022 revealed that many operators in the market are failing to back up their claims.

Verra, the leading carbon standard for the voluntary carbon market, is one such company striving to improve its approach. A nine-month investigation undertaken by the Guardian, the German weekly Die Zeit and SourceMaterial, a non-profit investigative journalism organisation, uncovered some serious doubts about Verra’s work.

The research found that 90% of Verra’s most common credits – rainforest offset credits – were “likely to be phantom credits and do not represent genuine carbon reductions”. The investigation found that 94% of the credits had no benefit to the climate and that threats to the forests where projects were based had “been overstated by about 400% on average”.

Verra, which certifies credits for major businesses including Shell and Disney, has heavily disputed the findings.

Inelastic demand

BNEF notes that ongoing initiatives such as the Integrity Council on Voluntary Carbon Markets are helping to spur developments, while some nations are introducing new guidance and regulations to finally create a sense of commonality around carbon markets.

BNEF notes that these groups will be critical to growing the market and highlighting that the correct use of high-quality credits can form a key part of corporate decarbonisation strategies. In this scenario, known as “inelastic demand”, businesses would be spurred to purchase credits, because they are confident they work, regardless of price. This demand could lead to 1.4bn credits purchased by corporates annually by 2030, reaching 5.9bn in 2050.

Indeed, the Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative (VCMI) has ramped up efforts to enroll businesses into what it believes is a best-practice scheme to navigate the market and ensure corporates are investing in “high-integrity” projects that provide assurances and negate the risk of greenwashing.

In November, just weeks before COP28, the VCMI announced the corporates that it would work with to accelerate the use of its claims code in a bid to clarify the credibility and usage of high-quality carbon credits that assist with decarbonisation.

Bain & Company, BCG, Better Drinks, Natura and Sendle are among the first members of the Early Adopters Program (EAP). The EAP gave the companies hands-on support to help them understand how the Claims Code works and provide tools and materials to aid communications about climate action claims and credit usage.

The VCMI argues that the Claims Code can bring integrity to the demand side of these markets. The Code has three tiers for companies to access – Platinum, Gold and Silver. Each tier recognises investments that contribute to emissions reductions and removals that are beyond corporate actions to meet science-based targets.

The VCMI has worked with the likes of the Greenhouse Gas Protocol (GHGP); Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi); the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Markets (ICVCM); and CDP to create a robust rulebook.

Greenstalled markets

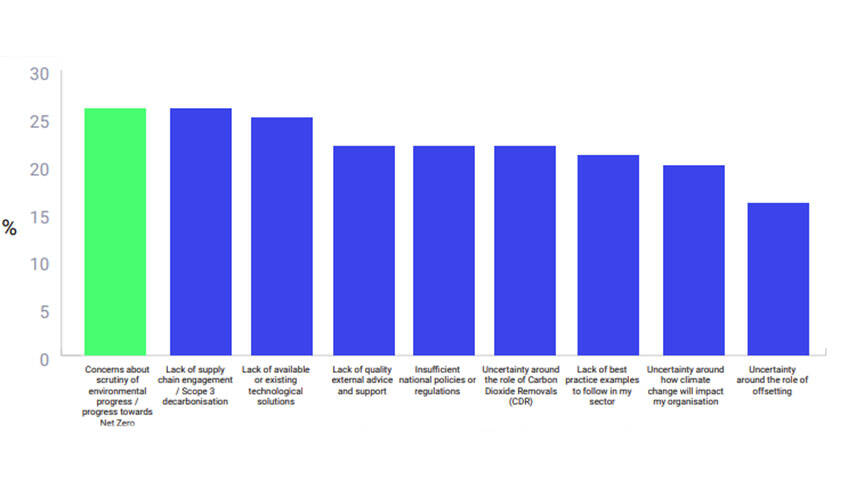

As new research from the Carbon Trust shows, however, businesses are still shying away from these markets, and other efforts to reach net-zero, because they are concerned about being criticised for their approaches to decarbonisation.

Known as “greenstalling”, this approach is when businesses intend to do the right thing by drastically ramping up decarbonisation efforts, but ultimately get stuck in “analysis paralysis” where they can’t find the right approach to doing it for fear of criticism.

Utilising carbon offsets was one of the main concerns that led to “greenstalling”, the research found. Alongside concerns around external scrutiny, lack of supplier engagement and insufficient policies, businesses cited “uncertainty around the role of offsetting” as a key barrier to net-zero.

Image: Carbon Trust

One thing that hasn’t helped these markets was COP28. It was hoped that the climate summit in Dubai in December would finally iron out all the issues with the delivery stage of national climate commitments, with a specific focus on how nations can interact with and utilise carbon markets, known as Article 6 of the Paris Agreement.

Article 6 covers both “compliance” markets, enabling nations to trade emissions credits garnered from reduction and removal activities with each other (under Article 6.2), and “hybrid” national-private markets, enabling countries to sell credits to businesses (under Article 6.4).

Article 6.2 is gradually replacing the existing Clean Development Mechanism; nations have been trading carbon credits for more than a decade already. But whether this has actually led to anywhere near the stated level of climate benefits is debatable.

Negotiations on Article 6 in Dubai ultimately failed. An agreement was not reached on two out of three of the key agenda items, representing another can kicked down the road to COP29; one that had already been kicked at COP27.

The final text calls on nations to submit their views by February 2024 on tools, guidance, baselines and additionality as to how nations should interact with carbon markets. It notes the establishment of a Supervisory Body that would draw up these parameters in a bid to finally shape a functioning market. However, key developments and decisions on “emissions avoidance” measures and calculations have been moved back to 2028.

Void of any real political clarity, many businesses may still be wary of engaging with the carbon markets.

For BNEF, the lack of progress at COP28 means that more companies may well turn to voluntary carbon markets to assist with decarbonisation plans. While this can boost market prospects, businesses will still need to be cautious as they venture to utilise carbon credits.

“The lack of progress at COP28 on Article 6 has been a wakeup call to the importance of the voluntary carbon market,” BNEF’s Harrison adds.

“The private sector has been hard at work to position carbon credits as a complement to a suite of other decarbonisation options, including the compliance market. Their success may just be the difference between the private sector achieving or not achieving its net-zero goals.”

Please login or Register to leave a comment.