Register for free and continue reading

Join our growing army of changemakers and get unlimited access to our premium content

Truss's objectives paper explicitly mentions the environment 180 times - but is it ambitious enough to meet the twin challenges of the climate and nature emergencies?

Since the prospect of Brexit was first raised, the issue of an FTA with the US has proven contentious – with supporters arguing that it could boost both economies as critics cite concerns over potential economic, social, political, health and safety and environment-related issues.

On the former, the UK-US total trade was valued at £220.9 billion last year, including 19.8% of all our exports. The Government’s analysis shows a UK-US FTA could increase trade between both countries by £15.3 billion in the long run and increase UK workers’ wages by £1.8 billion, against a 2018 baseline.

On the latter, criticisms have mounted in recent months after the UK legislated for a net-zero 2050 target and introduced policy packages such as the Environment Bill, Agriculture Bill and Resources and Waste Strategy while the Trump administration has busied itself formally exiting the Paris Agreement. The UK government had notably vowed to only seek FTAs with “like-minded” democracies.

To that end, edie is taking a deeper dive into the environmental provisions of Truss’s key negotiating objectives, which were published earlier today (2 March) and have sparked much debate on Twitter.

The broader picture

At a glance, it is promising to see that the objectives explicitly mention the environment 180 times.

The document stops short of time-bound numerical requirements at this stage but broadly states that: “Any agreement will ensure high standards and protections for consumers and workers, and will not compromise on our high environmental protection, animal welfare and food standards.”

The report notes that any potential UK-US FTA could impact the environment, but all outcomes are subject to negotiations. Changes in the UK’s production, for example, could see production ramp-up for lower-emission sectors. Changes to global trading patterns as a result of FTAs will likely impact transport emissions in some way. The UK Government claims in the document that any FTA “will not threaten the UK’s ability to meet its environmental commitments or its membership of international environmental agreements”.

It highlights the extent to which the UK public and UK business sphere do not wish to see environmental standards or labour provisions undercut.

On the former, the objectives state that any deal will “secure provisions that support and help further the Government’s ambition on climate change and achieving Net Zero carbon emissions by 2050, including promoting trade in low carbon goods and services, supporting research and development collaboration”.

On the latter, any deal must “Include measures which allow the UK to maintain the integrity, and provide meaningful protection, of world-leading environmental and labour standards” and “ensure parties do not waive or fail [these protections] in ways that create an artificial competitive advantage.

How has the US historically performed on climate and the environment?

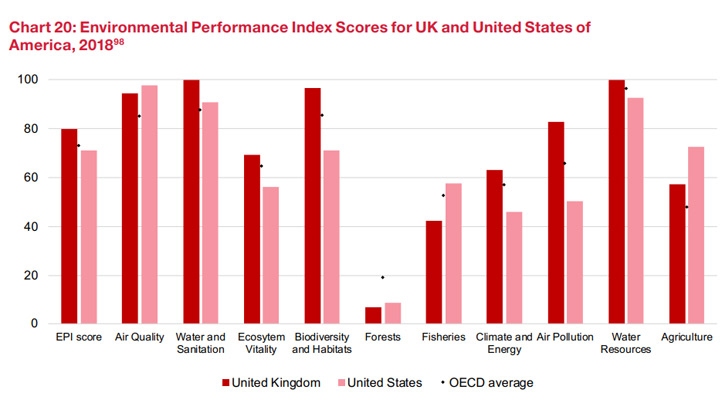

The Environmental Performance Index (EPI), an internationally comparable index of environmental variables, is used to outline each country’s environmental performance – states that the US’s overall score is below average for OECD nations, while the UK’s overall score is above average.

The US is currently performing better than the OECD average in just four of the 11 selected measures namely air quality, water and sanitation, fisheries and agriculture. It is around 20 points behind average on climate change.

Under the Paris Agreement, the US had pledged to reduce national emissions by 26-28% by 2025, against a 2005 baseline. The Obama Administration had also set a long-term ambition to reduce national net emissions by 80% by 2050, also against a 2005 baseline. The former of these targets will likely be scrapped once the US completes its withdrawal from the Paris Agreement. In either case, the US remains off-track to meeting either of these targets.

Looking at the US’s performance on an international stage, the nation is signed up to various multilateral agreements, including the Basel Convention, Stockholm Convention and UN Environment Programme. Moreover, the World Bank’s database on the content of trade agreements, previous US trade deals with other nations contain environmental regulations as part of any trade negotiations. The only exception to this is the US-Jordan agreement from 2001.

However, the US is also the second-largest emitter globally and is widely regarded as the global home of many trade lobbies which have hampered global progress so far – whether through finance, payments to policymakers of blocking climate talks.

Big oil, big plastics and big agriculture are all broadly considered Northern American corporate and political creations – and have received vocal support from the Trump Administration in recent years.

Will the FTA impact the UK’s emissions?

According to the document, a “simple preliminary and partial assessment” found that production outputs could create sectoral shifts that marginally ramp up production in a way that moves outputs from “relatively less CO2-intensive” sectors towards those that are more carbon-intensive. However, whether an overall increase in emissions results will largely depend on the energy mix at the time, and the UK is now sourcing more than half of its electricity needs from renewables.

“The impact of a UK-US FTA on CO2 emissions is uncertain but potential changes may result from a shift in economic output between more and less CO2-intensive sectors,” the report adds.

The FTA may also add additional costs to carbon-intensive businesses. Currently, UK power and heat generators, alongside energy-intensive industries and aircraft operators have to pay for emitted carbon under the EU Emissions Trading System and will continue to do so under a proposed UK replacement. For these sectors, the FTA document warns that any potential expansion in production could translate into “greater costs to business which is not captured in the modelling”. However, the assessment is unable to account for any efficiency gains across these sectors, or the adoption of low-carbon technologies.

On the transport front, international transport is estimated to be responsible for 33% of worldwide trade-related emissions, with shipping freight alone accounting for at least 3% of global emissions.

As the UK-US FTA is expected to increase the total value goods imported and exported between the two nations, the distance of transporting these goods increases. However, the document doesn’t confirm that this will result in an increase in transport emissions.

As transport emissions are aligned with the weight, rather than value of trade, a potential FTA could prioritise sectors where the £ per kg ratio is low, such as agriculture and energy, to sectors where it is high, such as electronic equipment. This, the report states, could actually reduce transport emissions.

Transport emissions will also be impacted by how the goods are transported, namely via sea or air freight, which are unable to be estimated in the assessment. There is also the possibility that increased UK-US bilateral trade can be displaced by prioritising geographical locations that are closer to the UK in future FTAs.

It is worth noting here that the UK Government has opted to exclude international shipping and aviation from accounting towards the UK’s net-zero target, against the advice of the Committee on Climate Change.

Will the FTA impact resource consumption and biodiversity?

With national governments meeting last month to try and piece together a global agreement to limit biodiversity loss and increased consumption of raw materials, the FTA has potential impacts in this area.

The UK Government claims it is committed to improving biodiversity through membership to the Convention on Biological Diversity and within its 25-Year Environment Plan. In the US, the 1973 Endangered Species Act is the primary statute under which biodiversity is governed. Both parties are also committed to Multilateral Environmental Agreements (MEAs), including the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

However, the FTA assessment findings suggest that primary resource consumption will likely increase as a result of further UK-US trade.

“All the scenarios modelled predict an increase in bilateral trade and increases in UK and US output and total trade,” the document states. “Additional production will result in increased use of resources – water, land and raw materials – and production of waste products. The modelling also estimates an increase in the output of the energy sector, and to a lesser extent, all agricultural sectors. These are typically land and resource-intensive production activities, which could negatively affect biodiversity through climate change, nutrient loading and pollution and ecosystem changes.”

The document does state that negative impacts “could be mitigated” through improved standards of production and that additional production could be the result of trade diversion from “less efficient producers based in countries with lower environmental standards” which could ultimately improve global biodiversity.

The document also adds that increased trade could result in air pollution from additional production and trade-related transport, but that increased pollution could be mitigated by Regional Trade Agreements (RTAs) – such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), Central American-Dominican Republic Free Trade Agreement. The document states that RTAs help boost incomes across different nations, and that “rising incomes as a result of free trade increase demand for environmental protections”. This, in turn, would help improve global air quality, despite any impact on regional air quality levels in the UK remaining undefined through the FTA document.

Expert reaction

Responding to the negotiating objectives paper, the Aldersgate Group’s executive director Nick Molho said that the documents “feature welcome language on climate and environmental policy, notably that the UK will aim to secure provisions that support the Government’s ambition on achieving net zero emissions and maintain both parties’ right to regulate in pursuit of decarbonisation”.

But in a word of caution, Molho added: “Looking forward, this ambition must be translated into binding and enforceable environmental provisions in any future FTAs negotiated by the UK, that in particular maintain our flexibility to introduce and tighten environmental rules and products’ standards over time. This will be essential to ensure the UK drives down emissions and improves the state of the environment in line with its net-zero target and future Environment Bill targets. An ambitious trade policy can also globalise the net-zero agenda and support the competitiveness of UK businesses as leading global providers of low carbon goods and services.”

To the latter point, the UK Government has vowed to use its position as COP26 host to call on other nations to set net-zero policy frameworks.

Greener UK chair Shaun Spiers shared Molho’s cautious optimism. He added: “It was good to see promises of high environmental, animal welfare and food safety standards, and that a UK-US trade deal won’t be allowed to undermine climate action. These ambitions will be crucial to the UK proving itself an environmental leader in the coming years.

“We will, however, be watching closely. The government is yet to put a commitment to maintaining existing standards in law. It is also important that a US trade deal does not jeopardise our ability to achieve a good deal with our nearest trading partners, the EU.”

Have your say…

//

Matt Mace and Sarah George

Please login or Register to leave a comment.